The Phantom of the Opera (1925 film)

| The Phantom of the Opera | |

|---|---|

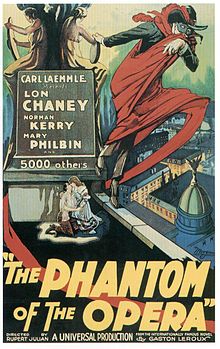

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Phantom of the Opera 1910 novel by Gaston Leroux |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Gustav Hinrichs |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

| Budget | $632,357.[1] |

| Box office |

|

The Phantom of the Opera is a 1925 American silent horror film adaptation of Gaston Leroux's novel of the same name directed by Rupert Julian and starring Lon Chaney in the title role of the deformed Phantom who haunts the Paris Opera House,[2] causing murder and mayhem in an attempt to make the woman he loves a star. The film remains most famous for Chaney's ghastly, self-devised make-up, which was kept a studio secret until the film's premiere. The picture also features Mary Philbin, Norman Kerry, Arthur Edmund Carewe, Gibson Gowland, John St. Polis and Snitz Edwards. The last surviving cast member was Carla Laemmle (1909–2014), niece of producer Carl Laemmle, who played a small role as a "prima ballerina" in the film when she was about 15 years old. The first cut of the film was previewed in Los Angeles on January 26, 1925. The film was released on September 6, 1925, premiering at the Astor Theatre in New York.

In 1953, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the film's distributor Universal Pictures did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication.

Plot

[edit]The following synopsis is based on the general release version of 1925, which has additional scenes and sequences in different order than the existing reissue print.

At the Paris Opera House, Comte Philippe de Chagny and his brother, the Vicomte Raoul de Chagny attend a production of Faust, where the latter's sweetheart, Christine Daaé, may sing. Raoul wishes for Christine to resign and marry him, but she prioritizes her career over their relationship.

Meanwhile, the former management has sold the opera house. While leaving, they tell the new managers about the Opera Ghost, a phantom who is "the occupant of box No. 5".

Mme. Carlotta, the prima donna, receives a letter from "The Phantom," demanding that Christine replace her the following night, threatening dire consequences if this does not happen. In Christine's dressing room, a voice tells her she must take Carlotta's place and think only of her career and her master.

The following day, Christine reveals to Raoul that she has been tutored by a mysterious voice, the "Spirit of Music," and it is now impossible to stop her career. Raoul says someone is probably playing a joke on her, and she storms off in anger.

That evening, Christine substitutes for Carlotta. During the performance, the managers are startled to see, seated in Box 5, a figure who later disappears. Simon Buquet then finds the body of his brother, stagehand Joseph Buquet, hanging by a noose and vows vengeance. Once again, a note from the Phantom demands Carlotta say she is ill and let Christine replace her. The managers get a similar note, reiterating that if Christine does not sing, they will present Faust in a cursed house.

The following evening, a defiant Carlotta sings. During the performance, the Phantom drops the chandelier hanging from the ceiling onto the audience, killing people. Christine enters a secret door behind the mirror in her dressing room, descending into the lower depths of the Opera. She meets the Phantom, who introduces himself as Erik and declares his love. Christine faints and he carries her to an underground suite fabricated for her comfort. The next day, she finds a note from Erik telling her that she must never look behind his mask. As he is preoccupied playing his organ, Christine playfully tears off his mask, revealing his deformed face. Enraged, the Phantom declares she is now his prisoner. She begs him to let her sing, and he relents, allowing her to visit the surface one last time if she promises not to see Raoul again.

Released, Christine meets with Raoul at the annual masked ball, where the Phantom appears disguised as the "Red-Death." On the roof of the Opera House, Christine tells Raoul about her experiences. Unbeknownst to them, the Phantom is listening nearby. Raoul swears to whisk Christine away to London following her next performance. As they leave the roof, a man with a fez approaches them. Aware that the Phantom awaits downstairs, he leads Christine and Raoul to another exit.

The next night, during her performance, Christine is kidnapped. Raoul rushes to her dressing room and meets the man in the fez again. He is actually Inspector Ledoux, a secret policeman who has been tracking Erik since he escaped as a prisoner from Devil's Island. After finding the secret door in Christine's room, the two men enter the Phantom's lair. They end up in a torture chamber of his design. Philippe also finds his way into the catacombs, looking for his brother, but is eventually drowned by Erik.

The Phantom subjects Raoul and Ledoux to intense heat. He then locks them in with barrels of gunpowder and causes the room to flood. Christine begs Erik to save Raoul, promising him anything in return, even becoming his wife. This causes the Phantom to save Raoul and Ledoux.

A mob led by Simon Buquet infiltrates Erik's lair. As they approach, the Phantom attempts to flee with Christine. Raoul saves Christine while Erik, in one last act of twisted showmanship, frightens the crowd by pretending to hold some kind of lethal entity in his clenched fist, only to reveal an empty palm before he is swarmed and killed by the mob and thrown into the Seine. Raoul and Christine later go on their honeymoon in Viroflay.

Cast

[edit]

- Lon Chaney as The Phantom

- Mary Philbin as Christine Daaé

- Norman Kerry as Vicomte Raoul de Chagny

- Arthur Edmund Carewe as Ledoux

- Gibson Gowland as Simon Buquet

- John St. Polis (credited as John Sainpolis) as Comte Philippe de Chagny

- Snitz Edwards as Florine Papillon

- Virginia Pearson as Carlotta

- Pearson played Carlotta's mother in the reshoot segments of the 1929 partial talkie reissue

- Mary Fabian played a talking Carlotta in the reshoot segments of the 1929 partial talkie reissue

Uncredited:

- Bernard Siegel as Joseph Buquet

- Edward Martindel as Comte Phillipe de Chagny

- for the reshoot segments of the 1929 partial talkie reissue

- Joseph Belmont as a stage manager

- Alexander Bevani as Méphistophélès

- Edward Cecil as Faust

- Ruth Clifford as ballerina

- Roy Coulson as the Jester

- George Davis as The guard outside Christine's door

- Madame Fiorenza as Box attendant

- Cesare Gravina as a retiring manager

- Bruce Covington as Monsieur Moncharmin

- William Humphrey as Monsieur Debienne

- George B Williams as Monsieur Ricard

- Carla Laemmle as Prima Ballerina

- Grace Marvin as Martha

- John Miljan as Valéntin

- Rolfe Sedan as an undetermined role

- William Tracy as the Ratcatcher, the messenger from the shadows

- Anton Vaverka as Prompter

- Julius Harris as Gaffer

Deleted scenes:

- Chester Conklin as Orderly

- Olive Ann Alcorn as La Sorelli

- Ward Crane as Count Ruboff

- Edith Yorke as Mama Valerius

- Vola Vale as Christine's Maid

Pre-production

[edit]

In 1922, Carl Laemmle, the president of Universal Pictures, took a vacation to Paris. During his vacation Laemmle met the author Gaston Leroux, who was working in the French film industry. Laemmle mentioned to Leroux that he admired the Paris Opera House. Leroux gave Laemmle a copy of his 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera. Laemmle read the book in one night and bought the film rights as a vehicle for actor Lon Chaney.[3] Production was scheduled for late 1924 at Universal Studios.

The filmmakers were unfamiliar with the layout of the Paris Opera House and consulted Ben Carré, a French art director who had worked at the Opera and was familiar with Leroux's novel. He said Leroux's depiction of the Opera cellars was based more on imagination than fact. Carré created twenty-four detailed charcoal sketches of the back and below-stage areas of the Opera, which the filmmakers replicated. Carré was in Europe when shooting began and had nothing more to do with the project; not until he was shown a print of the film in the 1970s did he realize his designs had been used.[4]: 37

The screenplay was written by Elliot J. Clawson, who had worked as the scenario writer of director Rupert Julian since 1916.[4]: 37 His first script was a close adaptation of Leroux and included scenes from the novel that never appeared in the released film, such as the Phantom summoning Christine to her father's grave in Brittany, where he poses in the cemetery as the "Angel of Music" and plays "The Resurrection of Lazarus" on his violin at midnight. The scene was filmed by Rupert Julian but excised after he left the project.[4]: 38

Inspired by the novel, Clawson added a lengthy flashback to Persia, where Erik (the Phantom) served as a conjurer and executioner in the court of a depraved Sultana, using his Punjab lasso to strangle prisoners. Falling from her favor, Erik was condemned to be eaten alive by ants. He was rescued by the Persian (the Sultana's chief of police, who became "Inspector Ledoux" in the final version of the film), but not before the ants had consumed most of his face.[4]: 38 The flashback was eliminated during subsequent story conferences, possibly for budgetary reasons. Instead, a line of dialogue was inserted to explain that Erik had been the chief torturer and inquisitor during the Paris Commune, when the Opera served as a prison, with no explanation of his damaged face.[4]: 39

The studio considered the novel's ending too low-key, but Clawson's third revised script retained the scene of Christine giving the Phantom a compassionate kiss. He is profoundly shaken and moans "Even my own mother would never kiss me." A mob approaches led by Simon (the brother of a stagehand who was murdered earlier by the Phantom). Erik flees the Opera House with Christine. He takes over a coach, which overturns thanks to his reckless driving, and then escapes the mob by scaling a bridge with the aid of his strangler's lasso. Waiting for him at the top is Simon, who cuts the lasso. The Phantom suffers a deadly fall. His dying words are "All I wanted... was to have a wife like anybody else... and to take her out on Sundays."[4]: 40

The studio remained dissatisfied. In another revised ending, Erik and Christine flee the mob and take refuge in her house. Before entering, Erik cringes "as Satan before the cross". Inside her rooms, he is overcome and says he is dying. He asks if she will kiss him and proposes to give her a wedding ring, so Christine can give it to Raoul. The Persian, Simon, and Raoul all burst into the house. Christine tells them Erik is ill; he slumps dead to the floor, sending the wedding ring rolling across the carpet. Christine sobs and flees to the garden; Raoul follows to console her.[4]: 40

Production

[edit]| Lon Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera | |

|---|---|

|

|

Production began in mid-October and did not go smoothly. According to director of photography Charles Van Enger, Chaney and the rest of the cast and crew had strained relations with director Rupert Julian. Eventually the star and director stopped talking, so Van Enger served as a go-between. He would report Julian's directions to Chaney, who responded "Tell him to go to hell." As Van Enger remembered, "Lon did whatever he wanted."[5]: 35

Rupert Julian had become Universal's prestige director by completing the Merry-Go-Round (1923) close to budget, after original director Eric von Stroheim had been fired. But on the set of The Phantom of the Opera his directorial mediocrity was obvious to the crew. According to Van Enger, Julian had wanted the screen to go black after the chandelier fell on the opera audience. Van Enger ignored him and lit the set with a soft glow, so the aftermath of the fall would be visible to the film audience.[5]: 36

The ending changed yet again during filming. The scripted chase scene through Paris was discarded in favor of an unscripted and more intimate finale.[4]: 40 To save Raoul, Christine agrees to wed Erik and she kisses his forehead. Erik is overcome by Christine's purity and his own ugliness. The mob enters his lair under the Opera House, only to find the Phantom slumped dead over his organ, where he had been playing his composition Don Juan Triumphant.[5]: 40

By mid-November 1924, the majority of Chaney's scenes had been filmed. Principal photography was completed just before the end of the year, with 350,000 feet of negative exposed. Editor Gilmore Walker assembled a rough cut of nearly four hours. The studio demanded a length of no more than 12 reels.[5]: 38

A score was prepared by Joseph Carl Breil. No information about the score survives other than Universal's release: "Presented with augmented concert orchestra, playing the score composed by Briel, composer of music for The Birth of a Nation". The exact quote from the opening day full-page ad in the Call-Bulletin read: "Universal Weekly claimed a 60-piece orchestra. Moving Picture World reported that 'The music from Faust supplied the music [for the picture].'"

The first cut of the film was previewed in Los Angeles on January 26, 1925. Audience reaction was extremely negative and summed up by the complaint "There's too much spook melodrama. Put in some gags to relieve the tension."[5]: 39 By March the studio had decided against the ending and decided the Phantom should not be redeemed by a woman's kiss: "Better to have kept him a devil to the end." The "redemptive" ending is now lost, with only a few frames still surviving.[5]: 40

The New York premiere was cancelled, and the film was rushed back into production, with a new script that focused more on Christine's love life. It is unknown whether Rupert Julian walked away from the production or was fired; in any case, his involvement with the film had ended. To salvage the film, Universal called upon the journeymen of its Hoot Gibson western unit, who worked cheaply and quickly.[5]: 40

Edward Sedgwick (later the director of Buster Keaton's 1928 film The Cameraman) was then assigned by producer Laemmle to direct a reshoot of the bulk of the film. Raymond L. Schrock and original screenwriter Elliot Clawson wrote new scenes at Sedgewick's request. The film was then changed from the dramatic thriller that was originally made into more of a romantic comedy with action elements. Most of the new scenes depicted added subplots, with Chester Conklin and Vola Vale as comedic relief to the heroes, and Ward Crane as the Russian Count Ruboff dueling with Raoul for Christine's affection. This version was previewed in San Francisco on April 26, 1925, and did not do well at all, with the audience booing it off of the screen. "The story drags to the point of nauseam", one reviewer stated.[citation needed]

The third and final version resulted from Universal holdovers Maurice Pivar and Lois Weber editing the production down to nine reels. Most of the Sedgwick material was removed, except for the ending, with the Phantom being hunted by a mob and then being thrown into the Seine River. Much of the cut Julian material was edited back into the picture, though some important scenes and characters were not restored. This version, containing material from the original 1924 shooting and some from the Sedgwick reworking, was then scheduled for release. It debuted on September 6, 1925, at the Astor Theatre in New York City.[6] The score for the Astor opening was to be composed by Professor Gustav Hinrichs. However, Hinrichs' score was not prepared in time, so instead, according to Universal Weekly, the premiere featured a score by Eugene Conte, composed mainly of "French airs" and the appropriate Faust cues.[Note 1] No expense was spared at the premiere; Universal even had a full organ installed at the Astor for the event. (As it was a legitimate house, the Astor theater used an orchestra, not an organ, for its music.)[citation needed] Vaudeville stars Broderick & Felsen created a live prologue for the film's Broadway presentation at the B.S. Moss Colony Theater beginning on November 28, 1925.[citation needed]

Makeup

[edit]Following the success of The Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1923, Chaney was once again given the freedom to create his own makeup, a practice which became almost as famous as the films he starred in.

Chaney commented "In The Phantom of the Opera, people exclaimed at my weird make-up. I achieved the Death's Head of that role without wearing a mask. It was the use of paints in the right shades and the right places—not the obvious parts of the face—which gave the complete illusion of horror ... It's all a matter of combining paints and lights to form the right illusion."[5]: 35

Chaney used a color illustration of the novel by Andre Castaigne as his model for the phantom's appearance. He raised the contours of his cheekbones by stuffing wadding inside his cheeks. He used a skullcap to raise his forehead height several inches and accentuate the bald dome of the Phantom's skull. Pencil lines masked the join of the skullcap and exaggerated his brow lines. Chaney then glued his ears to his head and painted his eye sockets black, adding white highlights under his eyes for a skeletal effect. He created a skeletal smile by attaching prongs to a set of rotted false teeth and coating his lips with greasepaint. To transform his nose, Chaney applied putty to sharpen its angle and inserted two loops of wire into his nostrils. Guide-wires hidden under the putty pulled his nostrils upward. According to cinematographer Charles Van Enger, Chaney suffered from his make-up, especially the wires, which sometimes made him "bleed like hell".[5]: 35

When audiences first saw the movie, they were said to have screamed or fainted during the scene where Christine pulls the concealing mask away, revealing his skull-like features.[citation needed]

Chaney's appearance as the Phantom in the film has been the most accurate depiction of the title character based on the description given in the novel, where the Phantom is described as having a skull-like face with a few wisps of black hair on top of his head.[citation needed] As in the novel, Chaney's Phantom has been deformed since birth, rather than having been disfigured by acid or fire, as in later adaptations of The Phantom of the Opera.[citation needed]

Soundstage 28

[edit]Producer Laemmle commissioned the construction of a set of the Paris Opera House. Because it would have to support hundreds of extras, the set became the first to be created with steel girders set in concrete. For this reason it was not dismantled until 2014.[3] Stage 28 on the Universal Studios lot still contained portions of the opera house set, and was the world's oldest surviving structure built specifically for a movie, at the time of its demolition. It was used in hundreds of movies and television series. In preparation for the demolition of Stage 28, the Paris Opera House set went through a preservation effort and was placed into storage. Stage 28 was completely demolished on September 23, 2014.[7][8]

Reception

[edit]Initial response

[edit]Initial critical response for the film was mostly positive. Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times gave the film a positive review as a spectacle picture, but felt that the story and acting may have been slightly improved.[9] TIME praised the sets but felt the picture was "only pretty good".[10] Variety wrote, "The Phantom of the Opera is not a bad film from a technical viewpoint, but revolving around the terrifying of all inmates of the Grand Opera House in Paris by a criminally insane mind behind a hideous face, the combination makes a welsh rarebit look foolish as a sleep destroyer."[11]

Modern response

[edit]

Roger Ebert awarded the film four out of four stars, writing "It creates beneath the opera one of the most grotesque places in the cinema, and Chaney's performance transforms an absurd character into a haunting one."[12] Adrian Warren of PopMatters gave the film 8/10 stars, summarizing, "Overall, The Phantom of the Opera is terrific: unsettling, beautifully shot and imbued with a dense and shadowy Gothic atmosphere. With such a strong technical and visual grounding it would have been difficult for Chaney to totally muck things up, and his performance is indeed integral, elevating an already solid horror drama into the realms of legendary cinema."[13] Time Out gave the film a mostly positive review, criticizing the film's "hobbling exposition", but praised Chaney's performance as being the best version of the title character, as well as the film's climax.[14]

TV Guide gave the film 4/5 stars, stating, "One of the most famous horror movies of all time, The Phantom of the Opera still manages to frighten after more than 60 years."[15] On Rotten Tomatoes, The Phantom of the Opera holds an approval rating of 90% based on 50 reviews from June 2002 to October 2020, with a weighted average rating of 8.3/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Decades later, it still retains its ability to scare – and Lon Chaney's performance remains one of the benchmarks of the horror genre."[16]

1929 reissue with sound

[edit]After the successful introduction of sound pictures during the 1928–29-movie season, Universal announced that they had secured the rights to a sequel to The Phantom of the Opera from the Gaston Leroux estate. Entitled The Return of the Phantom, Gaston Leroux himself was brought on-board to write the treatment for the film in which the phantom would survive his fate and come back to stalk Christine further, It's said that Leroux wrote this treatment with a tongue-in-cheek, self aware & satirical style, the picture would have sound and for the first time be in color.[17] Universal could not use Chaney in the film as he was now under contract at MGM.[18]

Universal later scrapped the sequel, and instead opted to reissue The Phantom of the Opera with a new synchronized score and sound effects track, as well as a few new dialog sequences. Directors Ernst Laemmle and Frank McCormick reshot little less than half of the picture with sound during August 1929, Some scenes from the film including the scene at the graveyard and original bal masque scenes were cut for this release and are now lost. The footage that was reused from the original film was scored with music arranged by Joseph Cherniavsky, and sound effects. Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry reprised their roles for the sound reshoot, and Edward Martindel, George B. Williams, Phillips Smalley, Ray Holderness, and Edward Davis were added to the cast to replace actors who were unavailable.[19] Universal was contractually unable to loop Chaney's dialogue, so another character was introduced who acts as a messenger for the Phantom in some scenes.[20] Because Chaney's talkie debut was eagerly anticipated by filmgoers, advertisements emphasised, "Lon Chaney's portrayal is a silent one!"[citation needed]

The sound version of Phantom opened on 15 December 1929.[21] While a financial success pulling in an additional million dollars for the studio, this version of the film was reportedly given a mixed to negative reception with most audiences being both underwhelmed and confused. It was particularly criticized by Lon Chaney who was reportedly angered by the decision to proceed without him and give his dialogue to a newly created assistant to the Phantom. This resulted in Chaney's relationship with Universal straining and contributed to his hesitancy to sign on to Dracula prior to his death.

The sound version is currently thought to most likely be lost as Universal's archived reels were reportedly burned in a studio fire in 1948, although the soundtrack discs survived, to which fans have produced extensive re-constructions since the film fell into the public domain.[22][23][unreliable source?]

The success of The Phantom of the Opera inspired Universal to finance the production of a long string of horror films through to the 1950s, starting with the base stories of Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933) and The Wolf Man (1941), and continuing with numerous sequels to all five films.[24]

Differences from the novel

[edit]Although this particular adaptation is often considered the most faithful, it contains some significant plot differences from the original novel.

In the movie, M. Debienne and M. Poligny transfer ownership of the Opera to M. Montcharmin and M. Richard, while in the novel they are simply the old and new managers.[25]

The character of Ledoux is not a mysterious Persian and is no longer a onetime acquaintance of the Phantom. He is now a French detective of the Secret Police. This character change was not originally scripted; it was made during the title card editing process.

The Phantom has no longer studied in Persia in his past. Rather, he is an escapee from Devil's Island and an expert in "the Black Arts".[citation needed]

As described in the "Production" section of this article, the filmmakers initially intended to preserve the original ending of the novel, and filmed scenes in which the Phantom dies of a broken heart at his organ after Christine leaves his lair. Because of the preview audience's poor reaction, the studio decided to change the ending to a more exciting chase sequence. Edward Sedgwick was hired to provide a climactic chase scene, with an ending in which the Phantom, after having saved Ledoux and Raoul, kidnaps Christine in Raoul's carriage. He is hunted down and cornered by an angry mob, who beat him to death and throw him into the Seine.

Preservation and home video status

[edit]

The finest quality print of the film existing was struck from an original camera negative for George Eastman House in the early 1950s by Universal Pictures. The original 1925 version survives only in 16mm "Show-At-Home" prints created by Universal for home movie use in the 1930s. There are several versions of these prints, but none of them are complete. All are from the original domestic camera negative.[20]

Because of the better quality of the Eastman House print, many home video releases have opted to use it as the basis of their transfers. This version has singer Mary Fabian in the role of Carlotta. In the reedited version, Virginia Pearson, who played Carlotta in the 1925 film, is credited and referred to as "Carlotta's Mother" instead. Most of the silent footage in the 1929 version is actually from a second camera, used to photograph the film for foreign markets and second negatives; careful examination of the two versions shows similar shots are slightly askew in composition in the 1929 version.[20] In 2009, ReelClassicDVD issued a special edition multi-disc DVD set which included a matched shot side-by-side comparison of the two versions, editing the 1925 Show-At-Home print's narrative and continuity to match the Eastman House print.[26]

For the 2003 Image Entertainment–Photoplay Productions two-disc DVD set, the 1929 soundtrack was reedited in an attempt to fit the Eastman House print as best as possible.[citation needed] However, there are some problems with this attempt. There is no corresponding "man with lantern" sequence on the sound discs. While the "music and effect" reels without dialogue seem to follow the discs fairly closely, the scenes with dialogue (which at one point constituted about 60% of the film) are generally shorter than their corresponding sequences on the discs.[citation needed] Also, since the sound discs were synchronized with a projection speed of 24 frames per second (the established speed for sound film), and the film on the DVD is presented at a slower frame rate (to reproduce natural speed), the soundtrack on the DVD set has been altered to run more slowly than the originally recorded speed.[citation needed] A trailer for the sound reissue, included for the first time on the DVD set, runs at the faster sound film speed, with the audio at the correct pitch.[citation needed]

On November 1, 2011, Image Entertainment released a new Blu-ray version of Phantom, produced by Film Preservation Associates, the film preservation company owned by David Shepard.[26]

On January 10, 2012, Shadowland Productions released The Phantom of the Opera: Angel of Music Edition, a two-disc DVD set featuring a newly recorded dialogue track with sound effects and an original musical score. The film was also reedited, combining elements from the 1925 version with the 1929 sound release. A 3D anaglyph version is included as an additional special feature.[27][promotional source?]

Eastman House print mystery

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

James Card, the curator of the Eastman House, obtained the Eastman print from a 35mm acetate print in 1950 from Universal. It is uncertain for what purpose the negative used to strike the Eastman House print was produced, as it includes footage from the 1929 sound reissue, and shows few signs of wear or damage. The fact that the print originally had a title card with a Western Electric Sound System credit, however, prove that it was intended as some sort of sound version. The removed title card included credits for cameramen, synchronization and score. Current extant copies of the Eastman print have a jump cut in the titles where this title once was.

For unknown reasons, an opening prologue showing a man with a lantern has been added—using a single continuous take—but no corresponding title cards or dialogue survive. This shot seems to have been a talking sequence, but it shows up in the original 1925 version, shorter in duration and using a different, close-up shot of the man with the lantern. Furthermore, the opening title sequence, the lantern man, the footage of Mary Fabian performing as Carlotta, and Mary Philbin's opera performances are photographed at 24 frames per second (sound film speed), and therefore were shot after the movie's original release. It is possible that the lantern man is meant to be Joseph Buquet, but the brief remaining close-up footage of this man from the 1925 version does not appear to be of Bernard Siegel, who plays Buquet. The man who appears in the reshot footage could be a different actor as well, but since there is no close-up of the man in this version, and the atmospheric lighting partially obscures his face, it is difficult to be certain.

While it was common practice to simultaneously shoot footage with multiple cameras for prints intended for domestic and foreign markets, the film is one of few for which footage of both versions survives (others include Buster Keaton's Steamboat Bill, Jr. and Charlie Chaplin's The Gold Rush). Comparisons of the two versions (both in black and white and in color) yield:

- Footage of most of the scenes shot from two slightly different angles

- Different takes for similar scenes

- 24 fps sound scenes replacing silent scene footage

- Variations in many rewritten dialogue and exposition cards, in the same font

Some possibilities regarding the negative's intended purpose are:

- It is an International Sound Version for foreign markets.

- It is a negative made for Universal Studios' reference.

International sound version

[edit]

"International sound versions" were sometimes made of films which the producing companies judged not to be worth the expense of reshooting in a foreign language. These versions were meant to cash in on the talkie craze; by 1930 anything with sound did well at the box office, while silent films were largely ignored by the public. International sound versions were basically part-talkies, and were largely silent except for musical sequences. Since the films included synchronized music and sound effect tracks, they could be advertised as sound pictures, and therefore capitalize on the talkie craze in foreign markets without the expense of reshooting scenes with dialogue in foreign languages.

To make an international version, the studio would simply replace any spoken dialogue in the film with music, and splice in some title cards in the appropriate language. Singing sequences were left intact, as well as any sound sequences without dialogue.

The sound discs for the International Sound Version are not known to be extant. The sound discs for the domestic sound version of The Phantom of the Opera are extant, but do not synchronize with the dialogue portions of the foreign version, which have been abbreviated on the Eastman House print. The International Sound Version is known to have played in Brazil as a reviews of it exists.[28] The International Sound Version is also known to have played in Italy and Germany as surviving reviews prove.[29] The existing print may therefore have been used as a master negative to strike prints to be sent overseas and then stored for safekeeping. This would explain why the Eastman House print shows no signs of negative wear.

Furthermore, the Eastman print originally had a Western Electric sound credit in the starting credits. This credit was removed by James Card who obtained the Eastman print from a 35mm acetate print in 1950 from Universal. In the edited Eastman print that is currently available, there is a jump cut, which removes the production credits including cameramen, synchronization and score. This same card carried the "Western Electric Sound System" credit.

Silent version

[edit]The (now missing) sound credit on the Eastman print proves that it could not have been a silent version. During the transition to sound in 1930, it was not uncommon for two versions of a picture, one silent and one sound, to play simultaneously (particularly for a movie from Universal, which kept a dual-format policy longer than most studios).

However, according to trade journals, no silent reissue was available. Harrison's Reports, which was always careful to specify whether or not a silent version of a movie was made, specifically stated that "there will be no silent version."[30]

Furthermore, no silent version was needed as the 1925 version was already silent. If a theatre not wired for sound wanted to show the film they would have had to exhibit the 1925 silent version.

Color preservation

[edit]According to Harrison's Reports, when the film was originally released, it contained 17 minutes of color footage; this footage was retained in the 1930 part-talking version.[31] Technicolor's records show 497 feet of color footage. Judging from trade journals and reviews, all of the opera scenes of Faust as well as the "Bal Masqué" scene were shot in Process 2 Technicolor (a two-color system).[citation needed] Prizmacolor sequences were also shot for the "Soldier's Night" introduction. Until recently, only the "Bal Masqué" scene survived in color; however in 2020, color footage of the ballet scene was found by the Dutch archive Eye Filmmuseum and uploaded to YouTube.[32] In the scene on the rooftop of the opera, the Phantom's cape was colored red, using the Handschiegl color process. This effect has been replicated by computer colorization in the 1996 restoration by Kevin Brownlow's Photoplay Productions.[33][20]

As with many silent films, black-and-white footage was tinted various colors to provide mood. These included amber for interiors, blue for night scenes, green for mysterious moods, red for fire, and yellow (sunshine) for daylight exteriors.[34]

Legacy

[edit]In 1998 The Phantom of the Opera was added to the United States National Film Registry, having been deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[35] It was included, at No. 52, in Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[36]

It is listed in the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[37]

In the United States, the film is in the public domain because Universal did not renew the copyright in 1953.[38]

See also

[edit]- List of cult films

- List of early color feature films

- List of films in the public domain in the United States

- Phantom of the Opera (1943 film)

- Universal Monsters

References

[edit]- Explanatory notes

- ^ Hinrichs' score was available by the time the film went into general release. (Reference: Music Institute of Chicago (2007) program note)

- Citations

- ^ Blake, Michael F. (1998). "The Films of Lon Chaney". Vestal Press Inc. p. 150. ISBN 1-879511-26-6.

- ^ Harrison's Reports film review; September 17, 1925, p. 151.

- ^ a b Preface to Forsyth, Frederick (1999). The Phantom of Manhattan. Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-04510-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h MacQueen, Scott (September 1989). "The 1926 Phantom of the Opera". American Cinematographer. 70 (9): 34–40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i MacQueen, Scott (October 1989). "Phantom of the Opera--Part II". American Cinematographer. 70 (19): 34–40.

- ^ "Lon Chaney Plays Role of Paris Opera Phantom". New York Times. September 6, 1925. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

The Phantom of the Opera, which has been many months in the making, is to be presented this evening at the Astor Theatre. We have told of the great stage effects, of the production of a section of the Paris Opera, with the grand staircase, the amphitheater, the back-stage scene – shifting devices and cellars associated with the horrors of the Second Commune. ...

- ^ Glass, Chris (August 26, 2014). "Historic Soundstage 28 Has Been Demolished". insideuniversal.net. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (August 28, 2014). "Universal to Demolish 'Phantom of the Opera' Soundstage, But Preserve Silent Film's Set". Variety. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Mordaunt Hall, "The Screen", The New York Times, September 7, 1925

- ^ "Cinema: The New Pictures September 21, 1925", TIME[dead link]

- ^ "The Phantom of the Opera – Variety". Variety. December 31, 1924. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 19, 2004). "Grand guignol and music of the night". Roger Ebert.com. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Warren, Adrian (February 11, 2014). "'The Phantom of the Opera' Is Unsettling and Imbued with a Dense and Shadowy Gothic Atmosphere". PopMatters. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Phantom of the Opera". Time Out. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Phantom of the Opera - Movie Reviews and Movie Ratings". TV Guide. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Phantom of the Opera". Rotten Tomatoes. October 2, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2024.

- ^ "'U' to Make 'Phantom' Sequel in Sound and Color". Film Daily, May 5, 1929, Pg. 1.

- ^ "Chaney Not For 'U' Sequel." Film Daily, May 17, 1929, p. 6.

- ^ "'Phantom' Dialogue Scenes Are Finished By Universal." Motion Picture News, August 24, 1929, p. 724.

- ^ a b c d "Versions and Sources of the Phantom of the Opera". Nerdly Pleasures. December 31, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2017 – via blogspot.com.

- ^ The Phantom of the Opera at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ Bailey, Logan (October 24, 2024). "The Phantom of the Opera (1929) Full Sound Version Reconstruction (2024)". YouTube.

- ^ The Phantom of the Opera (1925) – IMDb Trivia, retrieved October 27, 2024

- ^ Haining, Peter (1985). Foreword. The Phantom of the Opera. By Leroux, Gaston (1988 ed.). New York City: Dorset Press. pp. 15–19. ISBN 9-780-8802-9298-6. Retrieved November 18, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg E-text of The Phantom of the Opera, by Gaston Leroux". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Phantom of the Opera – Silent Era : Home Video Reviews". silentera.com.

- ^ The Masterpiece Of Silent Cinema Is Silent No Longer!

- ^ Review found in newspaper called Correio De Manha on the May 23, 1930 edition, p. 9.

- ^ La Patria del Friuli December 11, 1930 Issue. Available online at: Der Kinematograph January 1930 Issue.

- ^ Harrison's Reports film review; February 15, 1930, p. 26.

- ^ ""The Phantom of the Opera" (40% T-DN)". Harrison's Reports. New York. February 15, 1930. p. 26. Retrieved September 11, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bits & Pieces Nr. 182 (The Phantom of the Opera, 1925). Amsterdam: Eye Filmmuseum. September 17, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Phantom of the Opera". UK: Photoplay Productions. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Tinting and Toning of Motion Picture Film". www.brianpritchard.com. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Hooray for Hollywood – Librarian Names 25 More Films to National Registry" (Press release). Library of Congress. November 16, 1998. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments: 100 Scariest Moments in Movie History". Bravo TV. October 2004. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Steven Jay Schneider (2013). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Barron's. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-7641-6613-6.

- ^ Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–143. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.

- Bibliography

- Riley, Philip J. (1999). The making of the Phantom of the Opera: including the original 1925 shooting script (1. ed.). Absecon, NJ: MagicImage Filmbooks. ISBN 1882127331.

External links

[edit]- 1925 films

- 1925 horror films

- 1920s color films

- 1920s monster movies

- 1920s musical fantasy films

- American monster movies

- American silent feature films

- American black-and-white films

- Films based on The Phantom of the Opera

- Films directed by Rupert Julian

- Films directed by Edward Sedgwick

- Films directed by Lon Chaney

- Films about composers

- Films based on horror novels

- Films set in Paris

- Films set in a theatre

- Films about opera

- Silent films in color

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- Gothic horror films

- Films with screenplays by Bernard McConville

- Films produced by Carl Laemmle

- Surviving American silent films

- Early color films

- 1920s melodrama films

- American romantic horror films

- American romantic musical films

- Films about death

- 1920s dark fantasy films

- American musical fantasy films

- American psychological horror films

- American serial killer films

- 1920s English-language films

- 1920s American films

- Silent American horror films

- Silent American drama films

- 1920s horror drama films

- Part-talkie films

- English-language horror drama films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language musical fantasy films

- 1925 musical films