Night Moves (1975 film)

| Night Moves | |

|---|---|

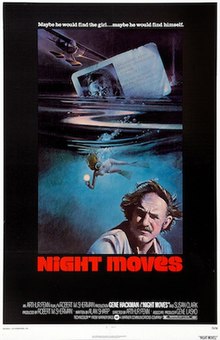

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Arthur Penn |

| Written by | Alan Sharp |

| Produced by | Robert M. Sherman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Dede Allen Stephen A. Rotter (co-editor)[1][2] |

| Music by | Michael Small |

Production companies | Hiller Productions, Ltd. – Layton[2] |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 99 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Night Moves is a 1975 American neo-noir film[3][4] directed by Arthur Penn, and starring Gene Hackman, Jennifer Warren, Susan Clark, with supporting performances from Melanie Griffith and James Woods. Its plot follows a Los Angeles private investigator who uncovers a series of sinister events while searching for the missing teenage daughter of a former movie actress.

Hackman was nominated for a BAFTA Award for his portrayal of private investigator Harry Moseby. The film has been called "a seminal modern noir work from the 1970s",[5] which refers to its relationship with the film noir tradition of detective films. The original screenplay is by Scottish writer Alan Sharp.

Although Night Moves was not considered particularly successful at the time of its release, it has attracted viewers and significant critical attention following its videotape and DVD releases.[6] In 2010, Manohla Dargis described it as "the great, despairing Night Moves (1975), with Gene Hackman as a private detective who ends up circling the abyss, a no‑exit comment on the post-1968, post-Watergate times."[7]

Plot

[edit]Harry Moseby is a retired professional football player now working as a private investigator in Los Angeles. He discovers that his wife Ellen is having a love affair with a man named Marty Heller.

Aging former actress Arlene Iverson hires Harry to find her sixteen-year-old daughter Delly Grastner. Arlene's only source of income is her daughter's trust fund, but it requires Delly to be living with her. Arlene gives Harry the name of one of Delly's friends in Los Angeles, a mechanic called Quentin. Quentin tells Harry that he last saw Delly at a New Mexico film location, where she started flirting with one of Arlene's old flames, stuntman Marv Ellman. Harry realizes that the injuries to Quentin's face are from fighting the stuntman and sympathizes with his bitterness towards Delly. He travels to the film location and talks to Marv and stunt coordinator Joey Ziegler. Before returning to Los Angeles, Harry is surprised to see Quentin working on Marv's stunt plane.

Harry suspects that Delly may be trying to seduce her mother's former lovers and travels to the Florida Keys, where her step-father Tom Iverson lives. Harry finds Delly staying with Tom and his girlfriend Paula. Harry, Paula, and Delly take a boat trip to go swimming, but Delly becomes distraught when she finds the submerged wreckage of a small plane with the decomposing body of the pilot inside. Paula marks the spot with a buoy, and when they return to shore, she appears to report the find to the Coast Guard. Later that night she visits Harry's cabin and the two have sex.

Harry persuades Delly to return to her mother in California. After he drops her off at her California home and sees her and her family fighting, he still is uneasy about the case. Later he listens to an answering-machine message from Delly apparently offering a tip, but he turns it off mid-message to focus on patching up his marriage. He tells his wife he will give up the agency, something she has wanted him to do for a long time.

Harry soon learns that Delly has been killed in a car accident on a movie set. Harry questions the driver of the car, Joey, who was seriously injured and is in a body cast. Joey lets him view footage of the crash, raising Harry's suspicions about Quentin the mechanic. Harry goes to the home of Arlene Iverson, who now stands to inherit her daughter's wealth, and finds her drunk by the pool, apparently not grief-stricken over the death of her daughter. Harry tracks down Quentin, who denies being the killer but says that Ellman was the dead pilot in the plane and was involved in smuggling. Quentin escapes before Harry can learn more.

Harry returns to Florida, where he finds Quentin's dead body floating in Tom's dolphin pen. Harry accuses Tom of the murder; they fight, and Tom is knocked unconscious. Paula admits she did not report the dead body in the plane because the aircraft contained a valuable sculpture they were smuggling piecemeal from the Yucatan to the United States. Harry and Paula set off to retrieve the relic. While Paula is diving, a seaplane arrives, and the pilot strafes the boat, machine-gunning Harry in the leg. The seaplane lands on the ocean, but when the pilot sees Paula surface with the sculpture, he taxies the plane over her and kills her. The impact of the pontoons on the surfaced sculpture flips the seaplane, and as the cockpit submerges, Harry is able to see through the glass window beneath his boat that the drowning pilot is Joey Ziegler, whose body is still in a cast from when he was in the accident that killed Delly. Bleeding profusely, Harry unsuccessfully tries to steer the boat, which is now going in circles.

Cast

[edit]- Gene Hackman as Harry Moseby

- Susan Clark as Ellen Moseby

- Jennifer Warren as Paula

- Edward Binns as Joey Ziegler

- Harris Yulin as Marty Heller

- Kenneth Mars as Nick

- Janet Ward as Arlene Iverson

- James Woods as Quentin

- Anthony Costello as Marv Ellman

- John Crawford as Tom Iverson

- Melanie Griffith as Delly Grastner

- Ben Archibek as Charles

- Dennis Dugan as boy

- C.J. Hincks as girl

- Maxwell Gail, Jr. as Stud

- Susan Barrister as ticket clerk

- Larry Mitchell as ticket clerk

Production

[edit]Night Moves was shot in the fall of 1973, but due to Melanie Griffith being just sixteen years of age at the time her underwater nude scenes were filmed, the movie was not released until 1975.[8] The role of Ellen, played by Susan Clark, was originally offered to Faye Dunaway who turned it down to star in Chinatown. Dunaway had just split from one of the film's stars - Harris Yulin - after a two year relationship. Night Moves's original title, Dark Tower, had to be changed so as to not confuse the film with the 1974 blockbuster hit The Towering Inferno. The house belonging to James Woods' character Quentin was owned by Phil Kaufman, road manager for Gram Parsons at the time of Parsons's death. Kaufman's subsequent actions became the basis for the 2003 film Grand Theft Parsons. The cast and crew of Night Moves were shooting at the house on the day the police came to question Kaufman, and as they were taking him away, Arthur Penn turned to Gene Hackman and said, "Man, we're shooting the wrong movie".

My Night at Maud's

[edit]A line from Night Moves occurs when Moseby declines an invitation from his wife to see the movie My Night at Maud's (1970): "I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kinda like watching paint dry."[9] The exchange from Night Moves was quoted in director Éric Rohmer's New York Times obituary in 2010.[10] Arthur Penn was an admirer of Rohmer's films;[11] Bruce Jackson has written an extended discussion of the role of My Night at Maud's in Night Moves; its protagonist and Moseby have related opportunities for infidelity, but respond differently.[9]

Release

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Roger Ebert gave the film a full four stars and called it "one of the best psychological thrillers in a long time, probably since Don't Look Now. It has an ending that comes not only as a complete surprise — which would be easy enough — but that also pulls everything together in a new way, one we hadn't thought of before, one that's almost unbearably poignant."[12] Ebert ranked Night Moves at No. 2 on his year-end list of the best films of 1975, behind only Nashville.[13] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that he had "mixed feelings" about the film, elaborating that the characters "seem to deserve better than the quality of the narrative given them. I can't figure out whether the screenplay by Alan Sharp was worked on too much or not enough, or whether Mr. Penn and his actors accepted the screenplay with more respect than it deserves."[14] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three stars out of four and stated that the protagonist is the "kind of mixed-up character" that "seems to be Hackman's specialty", while Alan Sharp's screenplay "provides the character of Paula (Jennifer Warren) with some of the best scripting for any woman this year".[15] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety called the film "a paradox. A suspenseless suspenser, very well cast with players who lend sustained interest to largely theatrical characters ... There's little rhyme or reason for the plot's progression, and the climax is far from stunning. But the curious aspect about the Warner Bros. release is that it plays well."[16] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times described the film as "a stunning, stylish detective mystery in the classic Raymond Chandler-Ross Macdonald mold," as well as "a fast, often funny movie with lots of compassionately observed real, living, breathing people.

This handsome Warners presentation is still another triumph for ever-busy, ever-versatile Gene Hackman, director Arthur Penn and writer Alan Sharp."[17] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post was negative, stating, "The fatal weakness is Alan Sharp's screenplay, a pointlessly murky, ambiguous variation on conventional private-eye themes ... we're supposed to be so impressed by the dolorous, world-weary tone that we overlook some pretty awesome loopholes and absurdities in the story itself, which never generates much mystery, suspense or credible human interest."[18]

Night Moves continues to attract critical attention long after its release. Film critic Michael Sragow included the film in his 1990 review collection entitled Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You've Never Seen.[19] Stephen Prince has written, "Penn directed a group of key pictures in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Alice's Restaurant (1969), Little Big Man (1970), Night Moves (1975)) that captured the verve of the counterculture, its subsequent collapse, and the ensuing despair of the post-Watergate era."[20] In his monograph, The Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg, Altman, Robert Kolker writes, "Night Moves was Penn's point of turning, his last carefully structured work, a strong and bitter film, whose bitterness emerges from an anxiety and from a loneliness that exists as a given, rather than a loneliness fought against, a fight that marks most of Penn's best work. Night Moves is a film of impotence and despair, and it marks the end of a cycle of films."[21]

Dennis Schwartz characterizes the film as "a seminal modern noir work from the 1970s" and adds, "This is arguably the best film that Arthur Penn has ever done."[5] This remark is telling in the context of Penn's earlier film, Bonnie and Clyde (1967), which is now considered a classic by most critics.[22] Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" list in 2006.[23] Jack Hawkins of Slash Film listed Night Moves among the most underrated films of the 1970s, describing the film as "a brilliant neo-noir that teems with salacious, jaded energy."[24]

Griffith's appearance in the movie garnered particular controversy for one racy nude scene that was shot when she was only 16 years old,[25] though she also appeared nude in other films such as Smile which was released the same year.[citation needed]

Night Moves has been classified by some critics as a "neo-noir" film, representing a further development of the film noir detective story.[3] Ronald Schwartz summarizes its role: "Harry Moseby is a man with limitations and weaknesses, a new dimension for detectives in the 1970s. Gone are the Philip Marlowes and tough-guy private investigators who have tremendous insight into crime and can triumph over criminals because they carry within them a code of honor. Harry cannot fathom what honor is, much less be subsumed by it."[4]

The film currently holds a score of 84% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 25 reviews.[26]

Box office

[edit]Night Moves was not a commercial success at the time of its 1975 theatrical release.[6][27]

Home media

[edit]Night Moves was released in 1992 in the U.S. as a LaserDisc[28] and as a VHS-format videotape.[29] In 2005, it was released as a DVD in the U.S. and Canada (region 1).[30] The DVD was favorably reviewed by Walter Chaw, who writes, "Shot through with grain and a certain, specific colour blanch I associate with the best movies from what I believe to be the best era in film history, Night Moves looks on Warner's DVD as good as it ever has, or, I daresay, should."[31] A region 2 DVD was released in 2007.[32] The film was released on Blu-ray in 2017 by Warner Archive Collection.[33]

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1975

- Florida locations where filming took place:

Further reading

[edit]- Berman, Emanuel (2001). "Arthur Penn's Night Moves: A Film that Interprets Us". In Gabbard, Glen O. (ed.). Psychoanalysis and Film. Karnac Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-85575-275-7.

- Emanuel Berman's extended interpretation of the film's screenplay.

- Meyer, David N. (May 3, 2009). "Any Kennedy: The Merciless, Blinding Sunshine of Night Moves". Film Noir of the Week. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

- David N. Meyer's review includes a fairly rare effort to parse Night Moves in terms of the contributions of its screenplay, directing, acting, etc.. Meyer particularly credits Gene Hackman's performance, Alan Sharp's writing, and Dede Allen's editing.

- Gear, Matthew Asprey (2019). Moseby Confidential: Arthur Penn's Night Moves and the Rise of Neo-Noir. Portland, Oregon: Jorvik Press. ISBN 978-0-9863770-8-2.

- Emphasizes Sharp's inspiration and conflicts with Penn. Based on interviews with Sharp's widow, Warren, Clark, and others.

References

[edit]- ^ Rotter was credited as "co-editor"; see "Index to Motion Picture Credits: Night Moves". Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.

- ^ a b c "Night Moves". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Sanders & Skoble 2008, p. 3.

- ^ a b Schwartz 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Dennis (December 5, 2000). "Night Moves". Ozus' World: Film Reviews. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ^ a b Slifkin 2004, p. 545.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (October 8, 2010). "Arthur Penn, a Director Attuned to His Country". The New York Times.

- ^ "Film Freedonia Film essays and commentary by Roderick Heath Night Moves 1975". 18 May 2019.

- ^ a b Jackson, Bruce (July 11, 2010). "Loose Ends in Night Moves". Senses of Cinema (55).

- ^ Kehr, David (January 11, 2010). "Éric Rohmer, a Leading Filmmaker of the French New Wave, Dies at 89". The New York Times.

- ^ Penn, Chaiken & Cronin 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 11, 1975). "Night Moves". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Ebert 2006, p. 443.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 12, 1975). "Screen: 'Night Moves' Stars a Private Eye More Complex Than His Case". The New York Times. 30.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (August 5, 1975). "Bleak, unique 'Night Moves'". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 5.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (March 26, 1975). "Film Reviews: Night Moves". Variety. 18.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (July 2, 1975). "Private Eye With Style". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (June 27, 1975). "Mysterious 'Night Moves'". The Washington Post. B7.

- ^ Sragow 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Prince 2002, p. 232.

- ^ Kolker 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 3, 1998). "Bonnie and Clyde (1967)". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

When I saw it, I had been a film critic for less than six months, and it was the first masterpiece I had seen on the job. I felt an exhilaration beyond describing. I did not suspect how long it would be between such experiences, but at least I learned that they were possible.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 26, 2006). "Great Movies: Night Moves". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ https://www.slashfilm.com/1126987/underrated-70s-movies-that-you-need-to-see/#:~:text=carnal%2C%20zeitgeisty%20energy.-,Night%20Moves%20(1975),-Warner%20Bros.%20Pictures

- ^ "Melanie Griffith won't see Fifty Shades of Grey film on Dakota Johnson's instruction". News.au.com. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018.

- ^ "Night Moves". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Kemp, Philip. "Arthur Penn". filmreference.com.

Penn established his reputation as a director with Bonnie and Clyde, one of the most significant and influential films of its decade. But since 1970 he has made only a handful of films, none of them successful at the box office. Night Moves and The Missouri Breaks, both poorly received on initial release, now rank among his most subtle and intriguing movies, and Four Friends, though uneven, remains constantly stimulating with its oblique, elliptical narrative structure.

- ^ Night Moves (LaserDisc). Warner Home Video. October 21, 1992. ISBN 0-7907-1309-8. 100 minutes. See "Night Moves (1975) [11102]". LaserDisc Database.

- ^ Night Moves (VHS tape). Warner Home Video. April 1, 1992. 100 minutes. See Night Moves [VHS] (1975). ASIN 630026887X.

- ^ Night Moves (DVD). Warner Home Video. July 12, 2005. 100 minutes. See "Night Moves (1975)". amazon.com.

- ^ Chaw, Walter (April 14, 2010). "Night Moves". Film Freak Central. Archived from the original on 2010-12-18.

- ^ Die heiße Spur (DVD). Warner Home Video. 21 September 2007. 96 minutes; German and English soundtracks. See "Die heiße Spur". amazon.de.

- ^ Reuben, Michael (August 15, 2017). "Night Moves Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com.

The raw 4K scan of Night Moves has been meticulously color-corrected by one of MPI's premier colorists, followed by WAC's customary cleanup to remove dust, blemishes and age-related damage. The result is a 1080p, AVC-encoded Blu-ray that ranks among the best and most accurate releases of a Seventies catalog title currently available.

Sources

[edit]- Ebert, Roger (2006). Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18201-8.

- Kolker, Robert (2000). The Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg, Altman (3rd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-512350-0.

- Penn, Arthur; Chaiken, Michael; Cronin, Paul (2008). Arthur Penn: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-105-7.

- Prince, Stephen (2002). A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbox (1980–1989). University of California. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-520-23266-2.

- Sanders, Steven; Skoble, Aeon G. (2008). The Philosophy of TV Noir. University of Kentucky Press. ISBN 978-0813172620.

- Slifkin, Irv (2004). VideoHound's groovy movies: far-out films of the psychedelic era. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-155-8.

- Schwartz, Ronald (2005). Neo-noir: The New Film Noir Style from Psycho to Collateral. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-5676-9.

- Sragow, Michael (1990). Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You've Never Seen. Mercury House. ISBN 978-0-916515-84-3.

External links

[edit]- 1975 films

- 1975 crime thriller films

- 1970s mystery thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American detective films

- American mystery thriller films

- Films directed by Arthur Penn

- Films scored by Michael Small

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Florida

- Warner Bros. films

- American neo-noir films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s English-language films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language mystery thriller films